ARCHITECTURES OF COLUMBIA.

1851-1857

THE STONE, BRICK, AND ADOBE

THE PROBLEM WITH COLUMBIA'S BUILDINGS.

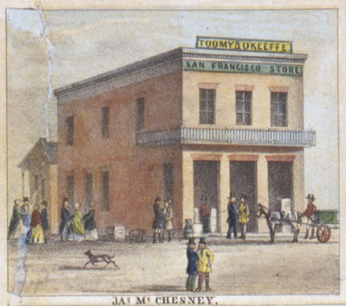

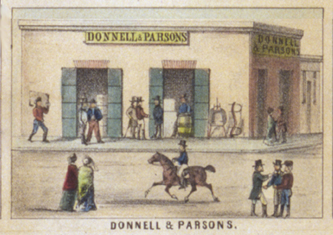

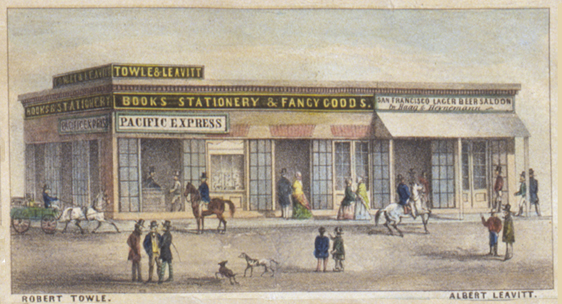

© Bancroft Library: from hand tinted view of Columbia 1855 drawing.

THE FIRST BRICK BUIDING IN COLUMBIA - 1855

The stone, brick, and adobe architectures of the Mother Lode region arose chiefly in response to the danger and the disaster of fire. The first settlements of the gold seekers were unplanned congested hodgepodges of canvas, (logs) and frame shelters. Open flame fires were necessary for heat, cooking, and illumination and even a minor accident could initiate a conflagration. A fire, once started, could scarcely ever be checked and the devastation of entire towns occurred time after time.

Every town had its volunteer fire department and some of the larger towns had several fire companies. Elaborate fire fighting equipment was imported (some of the hoses were to serve later in the first hydraulic* mining enterprises) and streets were required by ordinance to be wide enough to serve as fire lanes. But the primary danger still lay in the combustibility of building materials and the answer was found in the exploitation of architectural materials which are seldom used in other regions where ample stands of good timber are immediately at hand. Buildings designed for permanence were constructed of stone or brick or occasionally of adobe. Heavy raftered roofs were covered with metal and on top of this a thick layer of sand was deposited. Doors and windows were fitted with the distinctive sheet-iron shutters designed so that they could be closed in an emergency to protect the combustible interior furnishings.

(Note: even this was not a complete success as these buildings could cook like an oven and do damage to much inside the store. One building in Columbia's Fire of 1857 exploaded due to blasting powder; killing 6 men) These efforts were on the whole successful, as indicated by the number of such buildings which have survived the various conflagrations.

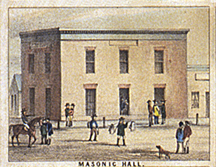

© Bancroft Library: from hand tinted view of Columbia 1855 drawing.

Masonic - 1855

Brick

was the favored building medium of the Americans. It symbolized for them substance and permanence and its prestige is reflected in the widespread use of brick facades for stone buildings. Some stone structures were also built by Americans for New Englanders. Middlewesterners were accustomed to building dry rock walls with stone cleared from fields; to building frame structures on stone foundations; and to lining cellar walls with mortar-laid stone. The stone masons par excellence were the Italians who came to the Gold fields.

The large number [of masonry buildings] - may be partly accounted for by the fact that the Sierras lies outside the earthquake region - walls are [sometimes] heavily coated with lime stucco - schist was employed because of its convenience rather than preference [especially in Sonora]

Limestone & Marble

is of very local occurrence, good exposures being noted at Columbia - some fine marble was quarried here in 1852 and shipped to San Francisco - E. R. Roberts of Stockton established a marble yard at Columbia in 1857, and in that year a block of Columbia marble was sent to the national capital to be put in the Washington Monument.

The first brickmaking in upper California was done in 1847 at the kiln of G. Zins established at Sutterville, just south of Sacramento - An advertisement by Stout and Walls, contract builders, in the Columbia Argus in 1854 offered brick at the kiln for $8 per thousand, $10 delivered, and $20 per thousand laid in the walls - examples illustrate the trend toward fireproof construction at the height of the Gold Rush.

Early lime kilns in which limestone was burned were situated at Shaws Flat (some of the Sonora and Columbia bricks were molded and fired here in the early 1850s)

Most of the stone buildings seen in our survey were built with mud mortar, or a mixture of mud and lime. Columbia had, in 1855, a brick reservoir lined with cement, and in 1856 Columbia had a building which was then unusual, if not unique for the Mother Lode, made of aggregate (concrete and gravel). It was destroyd in the 1860s in order to mine the gravels on which it stood.

Columbia is one of the architectural showplaces of the Mother Lode country. It was never abandoned; consequently the buildings never fell into complete disrepair; nor has it experienced the growth which led, in other towns, to false fronts and stucco covering. Almost all of its permanent buildings are made of brick, a reflection of the excellent brick-making lateritic clays available locally. Two brickyards (in operation in 1854) one was located - in Matelot Gulch - north of Columbia.

Columbia's first brick building, completed in 1853, was torn down in 1866 and the bricks were sold in Sonora.

Local residents, historian Aubrey Neasham, [and] a large number of printed books have been consulted in the effort to determine the names of builders and dates of erection of the stone structures.

R. Heizer and F. Fenenga 1948 Survey of Building Structures of the Sierran Gold Belt, 1848-70 - Bulletin 141, Geologic Guidebook The Mother Lode Country Along Highway 49 - Sierran Gold Belt. San Francisco: Department of Natural Resources.

*Hydraulic Mining in Columbia was more a box with water pressure to clean the ore and not used all that much to move earth from it's natural state.

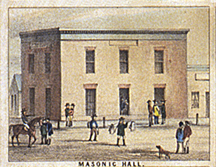

© Bancroft Library: from hand tinted view of Columbia 1855 drawing.

Towle & Leavitt - 1855

Painted Ladies

"Although once ubiquitous, exterior masonry finishes have largely been forgotten since the advent of the Industrial Revolution. For thousands of years before the development of inexpensive mechanical power, builders looked to materials close to their buildings sites. Hand tools and craft methods of production employed softer masonry materials that were less uniform in their physical properties than those produced industrially after the mid-nineteenth century. For the most part, these materials were covered with a variety of coatings and finishes to protect them from the weather and to permit the creation of finely finished exteriors.

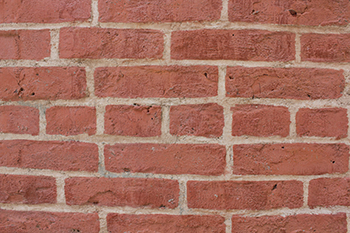

© Floyd D. P. Øydegaard - 2010

A sealed section of the San Francisco Store - 1855

"Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, the widespread availability of water and steam power, inexpensive overland transportation by railroad, and advances in engineering introduced inexpensive masonry materials that were both hard enough to withstand weather and that possessed finely finished surfaces intended to be exposed to view. Over the course of the subsequent one and one-half centuries, builders and property owners abandoned old masonry maintenance practices, eventually forgetting their utility and actively removing them in misguided efforts to restore what they incorrectly perceived as original surfaces. As a result, the majority of - pre-industrial masonry buildings - from major monuments to simple houses - have suffered physical damage. In addition, the appearance of most misrepresents our architectural heritage and would be unrecognizable to their builders and historic occupants."

Cummings, Abbott Lowell and R. Candee. "Colonial and Federal America: Accounts of Early Painting Practices." In Paint in America: the Colors of Historic Buildings, edited by Roger Moss. Washington, DC: The Preservation Press, 1994.

See also Archipedia New England for an in-depth report

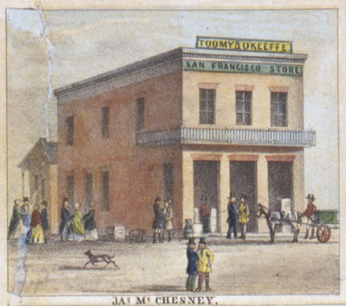

© Bancroft Library: from hand tinted view of Columbia 1855 drawing.

San Francisco Store - 1855

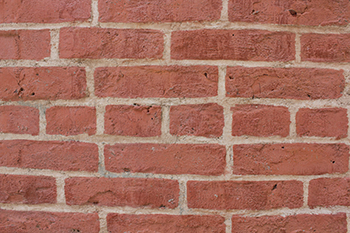

It is very apparent that builders from New England brought their knowledge to the western architecture. Research has shown that the bare bricks and mortar on all of the buildings in Columbia were painted to protect the walls from absorbing moisture, etc. Good examples can be seen with close scrutiny of the walls of certain buildings: San Francisco Store (corner of State and Parrots Ferry Road formerly Broadway), Hildenbrandt Builing (on Main Street) and the hand tinted Poster view of Columbia 1855.

These remaining examples show a definite area where the original brick and mortar were maticulously painted a sandier color than the regular brick mixture giving a more uniform and finished look. The hand tinted image also shows the difference between some areas of tinting and a different color for door.

Over the years the buildings went through "repaintings" of outside walls with drawings and signage to white painted walls. Some of these painted walls had their paint removed destroying the "protection" of the original surface.

Some minor research has shown that the bare bricks and mortar were painted to protect the walls from absorbing moisture. Good examples can be seen with close scrutiny of the walls of certain buildings

San Francisco Store corner of State and Parrots Ferry Road (formerly Broadway) and the hand tinted Poster view of Columbia 1855.

These remaining examples show a definite area where the origial brick and mortar were maticulously painted a sandier color than the regular brick mixture giving a more uniform and finished look. The hand tinted image also shows the difference between some areas of tinting and a different color for bricks above the door.

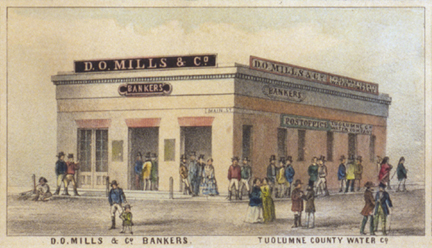

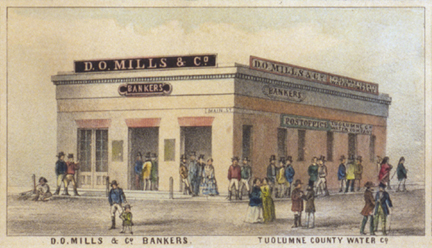

© Bancroft Library: from hand tinted view of Columbia 1855 drawing.

D. O. Mills Bank - 1855

This image of the bank shows the colors used to make the building more condusive to the enviornment. The blue-gray roof treatment at the top edge "blends" into the sky. The sand color seems to be two shades of "beige" paint. The "natural" brick color above the doors add to the possible four colors. These walls had to have been painted indidually and with great care.

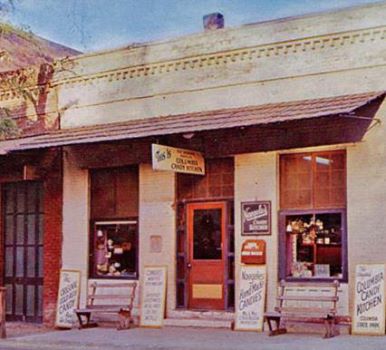

Naegeles Candy Kitchen - c1930s

Over the years the buildings (like Naegeles Candy Kitchen) went through "repaintings" of outside walls with drawings and signage to white painted walls. Some of these painted walls had their paint removed destroying the "protection" of the original surface.

(Naegeles Building orignally: D.O. Mills)

It is very apparent that builders from New England brought their knowledge to the western architecture. Research has shown that the bare bricks and mortar on all of the buildings in Columbia were painted to protect the walls from absorbing moisture, etc. Good examples can be seen with close scrutiny of the walls of certain buildings: San Francisco Store, corner of State and Parrotts Ferry Road (formerly Broadway) and Hildenbrandt Building (two story brick on Main Street, with original "sealer" paint still visible)

These remaining examples show a definite area where the origial brick and mortar were maticulously painted a sandier color than the regular brick mixture giving a more uniform and finished look. The hand tinted image also shows the difference between some areas of tinting and a different color for doors.

© Floyd D. P. Øydegaard. - 2010

A Section of the San Francisco Store showing sealed and unsealed - 1855

Over the years the buildings went through "repaintings" of outside walls with drawings and signage to white painted walls. Some of these painted walls had their paint removed destroying the "protection" of the original surface.

© Floyd D. P. Øydegaard. - 2010

A Header & Sleeper Section (painted) of the San Francisco Store - 1855

A sample of a well preserved section (sample above) of the San Francisco Store Building (State and Broadway/Parrott's Ferry) with "headers" center. Alas, the majority of the exterior walls have no protection. Built in 1854.

© Floyd D. P. Øydegaard. - 2010

Soderer and Marshall (paint removed), Hildenbrand Building (sealed/painted) - 1855

The example above shows the untreated brick (which shows the remnants of white paint) along side that which was treated

or hand painted and has survived over 160 years.

© Floyd D. P. Øydegaard. - 2010

Hildenbrand (background) & Meyer Building (foreground) - 1856

Here we show an extremely water damaged building in the foreground (Meyer Building) and a wall protected with the original "sealer" on a well preserved building (Hildenbrand Building)

This is a good example of the vast difference between a painted/protected surface and one that has been either not treated once painted and then had it's painted survice as well as the original treatment removed. (buildings are left to right: Soderer and Marshall, Hildenbrand Building.)

© Floyd D. P. Øydegaard.

Jack Douglass painted white - 1934.

Unfortunately the majority of the original buildings no longer have sealer nor any protecting finishes. Most sealers have been halted since 2001. The sad result is that there is internal damage in almost every building with severe ceiling damage, wall deteriation that causes mold and deterioation to the walls. Since the buildings were built on the ground, water wicks up on the inside. Giving the idea that the roofs leak from the top.

© Floyd D. P. Øydegaard.

Example of exterior wall of Artificers' Exchange - 2020.

Saint Charles Saloon - 1856

An example of stone (rubble) and mortar.

© Floyd D. P. Øydegaard - 2010

This page is created for the benefit of the public by

Floyd D. P. Øydegaard

Email contact:

fdpoyde3 (at) Yahoo (dot) com

A WORK IN PROGRESS,

created for the visitors to the Columbia State Historic park.

© Columbia State Historic Park & Floyd D. P. Øydegaard.